Usuari:Trollramsac/proves

| |

| |

| Dades clíniques | |

|---|---|

| Noms comercials | Hydra, Hyzyd, Isovit, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monografia |

| MedlinePlus | a682401 |

| Dades de llicència | US Daily Med:enllaç |

| Risc per l'embaràs | |

| Via | By mouth, intramuscular, intravenous |

| Codi ATC | J04AC01 J04 |

| Dades químiques i físiques | |

| Fórmula | C6H7N3O |

| Massa molecular | 137,14 g·mol−1 |

| Model 3D (Jmol) | Imatge interactiva |

C1=CN=CC=C1C(=O)NN | |

InChI=1S/C6H7N3O/c7-9-6(10)5-1-3-8-4-2-5/h1-4H,7H2,(H,9,10) Key:QRXWMOHMRWLFEY-UHFFFAOYSA-N | |

| Estat legal | |

| R. dispensació |

|

| Dades farmacocinètiques | |

| Unió proteica | Very low (0–10%) |

| Metabolisme | liver; CYP450: 2C19, 3A4 inhibitor |

| Vida mitjana | 0.5–1.6h (fast acetylators), 2-5h (slow acetylators) |

| Excreció | urine (primarily), feces |

| Identificadors | |

Pyridine-4-carbohydrazide

| |

| Sinònims | isonicotinic acid hydrazide, isonicotinyl hydrazine, INHA |

| Número CAS | 54-85-3 |

| PubChem (CID) | 3767 |

| DrugBank | DB00951 |

| ChemSpider | 3635 |

| UNII | V83O1VOZ8L |

| KEGG | D00346 C07054 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:6030 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL64 |

| NIAID ChemDB | 007657 |

La isoniazida, també coneguda com a hidrazida de l'àcid isonicotínic (INH), és un antibiòtic emprat pel tractament de la tuberculosis[3]. En el cas de la tuberculosi activa, s'empra sovint juntament amb rifampicina, pirazinamida i estreptomicina o etambutol[4]. En el cas de la tuberculosi latent sovint s'empra exclusivament.[2] També pot ser emprat amb micobacteris no tuberculosos, com M. avium, M. kansasii o M. xenopi.[2] Habitualment es pren per via oral, però també es pot administrar per injecció intramuscular.[2]

Els efectes adversos més comuns inclouen hipertransaminasèmia i entumiment a mans i peus.[2] Els efectes adversos greus poden incluir hepatitis i insuficiència hepàtica aguda.[2] És incert si el seu ús durant l'embaràs és segur pel fetus[5], encarà que el seu ús durant la lactància és probablement segur.[5] Es pot administrar piridoxina per reduir el risc d'efectes adversos.[6] La isoniazida actua parcialment mitjançant la disrupció de la formació de la paret cel·lular bacteriana, comportant la mort cel·lular.[2]

La isoniazida va ser fabricada per primera vegada el 1952.[7] Està inclosa a la Llista model de Medicaments essencials de l'Organització Mundial de la Salut.[8] L'Organització Mundial de la Salut ha classificat la isoniazida com un antimicrobià d'importància crítica per la medicina humana.[9] La isoniazida es troba disponible com a medicament genèric.[2]

Usos mèdics

[modifica]Tuberculosi

[modifica]La isoniazida s'empra sovint per tractant infeccions tuberculoses actives i latents. En pacients amb una infecció per Mycobacterium tuberculosis sensible a isoniazida, els règims terapèutics basats en isoniazida són habitualment efectius quan existeix una adherència correcta al tractament. No obstant això, en pacients amb una infecció per Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistent a isoniazida, els règims terapèutics exclusivament basats en isoniazida tenen una taxa alta de fracàs terapèutic.[10]

La isoniazida ha estat aprovada com a tractament profilàctic per a les següents poblacions:

- Pacients amb infecció VIH i una reacció PPD (derivat proteic purificat) d'induració d'almenys 5 mm.

- Contactes de pacient amb tuberculosis que tenen una reacció PPD d'induració d'almenys 5 mm.

- Persones amb reaccions PPD inicialment negatives que esdevenen positives en un període de 2 anys – induració d'almenys 10 mm per aquells d'edat menor a 35 anys, induració d'almenys 15 mm per aquells amb edat superior a 35 anys.

- Persones amb dany pulmonar en una radiografia de tòrax possiblement degut a una tuberculosi curada i que també tenen una reacció PPD d'induració d'almenys 5 mm.

- Usuaris de drogues parenterals amb un estatus VIH negatiu que tenen una reacció PPD d'induració d'almenys 10 mm.

- Persones amb una reacció PPD d'induració d'almenys 10 mm, d'origen estranger provinents de regions amb alta prevalença i baix nivell socioeconòmic.

- Pacients que resideixen en instituticions de llarga estada.[11][12]

La isoniazida es pot emprar de manera aïllada o en combinació amb rifampicina pel tractament de tuberculosi latent, o com a part d'un règim terapèutic de 4 fàrmacs per a tuberculosi activa.[13] El règim terapèutic típicament requereix administració oral diària o setmanal durant un períod de 3 - 9 mesos, sovint sota supervisió de tipus Tractament Directament Observat (TDO).[13]

Micobactèria no tuberculosa

[modifica]La isoniazida s'ha emprat amplament en el tractament de Mycobacterium avium complex com a part d'un règim que inclou rifampicina i etambutol.[14] L'evidència suggereix que la isoniazida prevé la síntesi d'àcid micòlic en M. avium complex de manera anàloga a M. tuberculosis[15] i, malgrat no té efecte bactericida en M. avium complex, potencia marcadament l'efecte de la rifampicina. La introducció dels macròlids ha portat a una gran reducció d'aquest ús. Tanmateix, a causa de la infradosificació habitual de la rifampicina en el tractament de M. avium complex, l'existència d'aquest efecte pot obrir noves línies d'investigació[16]

Poblacions especials

[modifica]It is recommended that women with active tuberculosis who are pregnant or breastfeeding take isoniazid. Preventive therapy should be delayed until after giving birth.[17] Nursing mothers excrete a relatively low and non-toxic concentration of INH in breast milk, and their babies are at low risk for side effects. Both pregnant women and infants being breastfed by mothers taking INH should take vitamin B6 in its pyridoxine form to minimize the risk of peripheral nerve damage.[18] Vitamin B6 is used to prevent isoniazid-induced B6 deficiency and neuropathy in people with a risk factor, such as pregnancy, lactation, HIV infection, alcoholism, diabetes, kidney failure, or malnutrition.[19]

People with liver dysfunction are at a higher risk for hepatitis caused by INH, and may need a lower dose.[17]

Levels of liver enzymes in the bloodstream should be frequently checked in daily alcohol drinkers, pregnant women, IV drug users, people over 35, and those who have chronic liver disease, severe kidney dysfunction, peripheral neuropathy, or HIV infection since they are more likely to develop hepatitis from INH.[17][20]

Side effects

[modifica]Up to 20% of people taking isoniazid experience peripheral neuropathy when taking doses of 6 mg/kg of weight daily or higher.[21] Gastrointestinal reactions include nausea and vomiting.[11] Aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and agranulocytosis due to lack of production of red blood cells, platelets, and white blood cells by the bone marrow respectively, can also occur.[11] Hypersensitivity reactions are also common and can present with a maculopapular rash and fever.[11] Gynecomastia may occur.[13]

Asymptomatic elevation of serum liver enzyme concentrations occurs in 10% to 20% of people taking INH, and liver enzyme concentrations usually return to normal even when treatment is continued.[22] Isoniazid has a boxed warning for severe and sometimes fatal hepatitis, which is age-dependent at a rate of 0.3% in people 21 to 35 years old and over 2% in those over age 50.[11][23] Symptoms suggestive of liver toxicity include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, right upper quadrant pain, and loss of appetite.[11] Black and Hispanic women are at higher risk for isoniazid-induced hepatotoxicity.[11] When it happens, isoniazid-induced liver toxicity has been shown to occur in 50% of patients within the first 2 months of therapy.[24]

Some recommend that liver function should be monitored carefully in all people receiving it,[17] but others recommend monitoring only in certain populations.[22][25][26]

Headache, poor concentration, weight gain, poor memory, insomnia, and depression have all been associated with isoniazid use.[27] All patients and healthcare workers should be aware of these serious side effects, especially if suicidal ideation or behavior are suspected.[27][28][29]

Isoniazid is associated with pyridoxine (vitamin B6) deficiency because of its similar structure. Isoniazid is also associated with increased excretion of pyridoxine. Pyridoxal phosphate (a derivative of pyridoxine) is required for δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase, the enzyme responsible for the rate-limiting step in heme synthesis. Therefore, isoniazid-induced pyridoxine deficiency causes insufficient heme formation in early red blood cells, leading to sideroblastic anemia.[19]

Drug interactions

[modifica]People taking isoniazid and acetaminophen are at risk of acetaminophen toxicity. Isoniazid is thought to induce a liver enzyme which causes a larger amount of acetaminophen to be metabolized to a toxic form.[30][31]

Isoniazid decreases the metabolism of carbamazepine, thus slowing down its clearance from the body. People taking carbamazepine should have their carbamazepine levels monitored and, if necessary, have their dose adjusted accordingly.[32]

It is possible that isoniazid may decrease the serum levels of ketoconazole after long-term treatment. This is seen with the simultaneous use of rifampin, isoniazid, and ketoconazole.[33]

Isoniazid may increase the amount of phenytoin in the body. The doses of phenytoin may need to be adjusted when given with isoniazid.[34][35]

Isoniazid may increase the plasma levels of theophylline. There are some cases of theophylline slowing down isoniazid elimination. Both theophylline and isoniazid levels should be monitored.[36]

Valproate levels may increase when taken with isoniazid. Valproate levels should be monitored and its dose adjusted if necessary.[34]

Mechanism of action

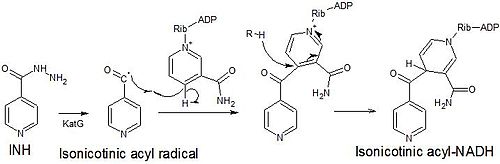

[modifica]Isoniazid is a prodrug that inhibits the formation of the mycobacterial cell wall. Isoniazid must be activated by KatG, a bacterial catalase-peroxidase enzyme in Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[37] KatG catalyzes the formation of the isonicotinic acyl radical, which spontaneously couples with NADH to form the nicotinoyl-NAD adduct. This complex binds tightly to the enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase InhA, thereby blocking the natural enoyl-AcpM substrate and the action of fatty acid synthase. This process inhibits the synthesis of mycolic acids, which are required components of the mycobacterial cell wall. A range of radicals are produced by KatG activation of isoniazid, including nitric oxide,[38] which has also been shown to be important in the action of another antimycobacterial prodrug pretomanid.[39]

Isoniazid is bactericidal to rapidly dividing mycobacteria, but is bacteriostatic if the mycobacteria are slow-growing.[40] It inhibits the cytochrome P450 system and hence acts as a source of free radicals.[41]

Isoniazid is a mild monoamine oxidase inhibitor(MAO-I).[42]

Metabolism

[modifica]Isoniazid reaches therapeutic concentrations in serum, cerebrospinal fluid, and within caseous granulomas. It is metabolized in the liver via acetylation into acetylhydrazine. Two forms of the enzyme are responsible for acetylation, so some patients metabolize the drug more quickly than others. Hence, the half-life is bimodal, with "slow acetylators" and "fast acetylators". A graph of number of people versus time shows peaks at one and three hours. The height of the peaks depends on the ethnicities of the people being tested. The metabolites are excreted in the urine. Doses do not usually have to be adjusted in case of renal failure.

History

[modifica]First synthesis was described in 1912. A. Kachugin invented the drug against tuberculosis under name Tubazid. Three pharmaceutical companies unsuccessfully attempted to patent the drug at the same time,[43] the most prominent one being Roche, which launched its version, Rimifon, in 1952.[44] With the introduction of isoniazid, a cure for tuberculosis was first considered possible.

The drug was first tested at Many Farms, a Navajo community in Arizona, due to the Navajo reservation's tuberculosis problem and because the population had not previously been treated with streptomycin, the main tuberculosis treatment at the time.[45] The research was led by Walsh McDermott, an infectious disease researcher with an interest in public health, who had previously taken isoniazid to treat his own tuberculosis.[46]

Isoniazid and a related drug, iproniazid, were among the first drugs to be referred to as antidepressants.[47]

Preparation

[modifica]Isoniazid is an isonicotinic acid derivative. It is manufactured using 4-cyanopyridine and hydrazine hydrate.[48] In another method, isoniazid was claimed to have been made from citric acid starting material.[49]

Brand names

[modifica]Hydra, Hyzyd, Isovit, Laniazid, Nydrazid, Rimifon, and Stanozide.[50]

Altres usos

[modifica]Chromatography

[modifica]Isonicotinic acid hydrazide is also used in chromatography to differentiate between various degrees of conjugation in organic compounds barring the ketone functional group.[51] The test works by forming a hydrazone which can be detected by its bathochromic shift.

Dogs

[modifica]Isoniazid may be used for dogs, but there have been concerns it can cause seizures.[52]

Referències

[modifica]- ↑ 1,0 1,1 «Isoniazid (Nydrazid) Use During Pregnancy». Drugs.com, 07-10-2019. [Consulta: 24 gener 2020].

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 2,2 2,3 2,4 2,5 2,6 2,7 «Isoniazid». The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Arxivat de l'original el 20 December 2016. [Consulta: 8 desembre 2016].

- ↑ «Isoniacida» (en castellà). Asociación Española de Pediatría, 17-08-2015. [Consulta: 24 setembre 2020].

- ↑ WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization, 2009, p. 136. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ↑ 5,0 5,1 «Isoniazid (Nydrazid) Use During Pregnancy». www.drugs.com. Arxivat de l'original el 20 December 2016. [Consulta: 10 desembre 2016].

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart. Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2015, p. 49. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ Walker, S. R. [2017-09-10]. Trends and Changes in Drug Research and Development. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, p. 109. ISBN 9789400926592.

- ↑ World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine. 6th revision. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. ISBN 9789241515528.

- ↑ «Treatment of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis with first-line drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis». Lancet Infect Dis, vol. 17, 2, 2-2017, pàg. 223–234. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30407-8. PMID: 27865891.

- ↑ 11,0 11,1 11,2 11,3 11,4 11,5 11,6 «Isoniazid (package insert)».

- ↑ «The Use of Preventive Therapy for Tuberculosis Infection in the United States – Recommendations of the Advisory Committee for Elimination of Tuberculosis». Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, vol. 39 (RR-8), 18-05-1990, pàg. 9–12 [Consulta: 22 febrer 2016].

- ↑ 13,0 13,1 13,2 Lewis, Sharon Mantik. Medical-surgical nursing : assessment and management of clinical problems. Dirksen, Shannon Ruff,, Heitkemper, Margaret M. (Margaret McLean),, Bucher, Linda,, Harding, Mariann. Ninth, 5 December 2013. ISBN 978-0-323-10089-2. OCLC 228373703.

- ↑ «First randomised trial of treatments for pulmonary disease caused by M avium intracellulare, M malmoense, and M xenopi in HIV negative patients: Rifampicin, ethambutol and isoniazid versus rifampicin and ethambutol». Thorax, vol. 56, 3, 2001, pàg. 167–72. DOI: 10.1136/thorax.56.3.167. PMC: 1758783. PMID: 11182006.

- ↑ Mdluli, K; Swanson, J; Fischer, E; Lee, R. E; Barry Ce, 3rd «Mechanisms involved in the intrinsic isoniazid resistance of Mycobacterium avium». Molecular Microbiology, vol. 27, 6, 1998, pàg. 1223–33. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00774.x. PMID: 9570407.

- ↑ Van Ingen, J; Egelund, E. F; Levin, A; Totten, S. E; Boeree, M. J; Mouton, J. W; Aarnoutse, R. E; Heifets, L. B; Peloquin, C. A «The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease treatment». American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 186, 6, 2012, pàg. 559–65. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0682OC. PMID: 22744719.

- ↑ 17,0 17,1 17,2 17,3 «Isoniazid tablet». DailyMed, 18-10-2018. Arxivat de l'original el 13 March 2019. [Consulta: 24 gener 2020].

- ↑ Bothamley, G. «Drug treatment for tuberculosis during pregnancy: safety considerations». Drug Safety, vol. 24, 7, 2001, pàg. 553–565. DOI: 10.2165/00002018-200124070-00006. PMID: 11444726.

- ↑ 19,0 19,1 Steichen, O.; Martinez-Almoyna, L.; De Broucker, T. «Isoniazid induced neuropathy: consider prevention». Revue des Maladies Respiratoires, vol. 23, 2 Pt 1, 4-2006, pàg. 157–160. DOI: 10.1016/S0761-8425(06)71480-2. PMID: 16788441.

- ↑ Saukkonen, J.J.; Cohn, D.L.; Jasmer, R.M. «An official ATS statement: hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis therapy». American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 174, 8, 15-10-2006, pàg. 935–952. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1666ST. PMID: 17021358.

- ↑ Alldredge, Brian. Applied Therapeutics, February 12, 2013. ISBN 9781609137137.

- ↑ 22,0 22,1 «Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Guide for Primary Health Care Providers». cdc.gov. Center for Disease Control. Arxivat de l'original el 25 March 2016. [Consulta: 25 març 2016].

- ↑ Trevor, A. & Katzung, B. (2013). Katzung & Trevor's Pharmacology: examination & board review (10th ed., p. 417). New York. McGraw-Hill Medical, Lange.

- ↑ «Isoniazid UpToDate». Arxivat de l'original el 2015-10-25.

- ↑ «Treatment of Tuberculosis – Guidelines (4th ed.)». who.int. World Health Organization. Arxivat de l'original el 4 April 2016. [Consulta: 25 març 2016].

- ↑ «Chemotherapy and management of tuberculosis in the United Kingdom: recommendations 1998. Joint Tuberculosis Committee of the British Thoracic Society». Thorax, vol. 53, 7, 7-1998, pàg. 536–548. DOI: 10.1136/thx.53.7.536. PMC: 1745276. PMID: 9797751.

- ↑ 27,0 27,1 «Isoniazid-induced psychosis». Annals of Pharmacotherapy, vol. 32, 9, 9-1998, pàg. 889–891. DOI: 10.1345/aph.17377. PMID: 9762376.

- ↑ Iannaccone, R.; Sue, Y.J.; Avner, J.R. «Suicidal psychosis secondary to isoniazid». Pediatric Emergency Care, vol. 18, 1, 2002, pàg. 25–27. DOI: 10.1097/00006565-200202000-00008. PMID: 11862134.

- ↑ «Isoniazid-associated psychosis: case report and review of the literature». Annals of Pharmacotherapy, vol. 27, 2, 2-1993, pàg. 167–170. DOI: 10.1177/106002809302700205. PMID: 8439690.

- ↑ Murphy, R.; Swartz, R.; Watkins, P.B. «Severe acetaminophen toxicity in a patient receiving isoniazid». Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 113, 10, 15-11-1990, pàg. 799–800. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-10-799. PMID: 2240884.

- ↑ Burk, R.F.; Hill, K.E.; Hunt Jr., R.W.; Martin, A.E. «Isoniazid potentiation of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in the rat and 4-methylpyrazole inhibition of it». Research Communications in Chemical Pathology and Pharmacolog, vol. 69, 1, 7-1990, pàg. 115–118. PMID: 2218067.

- ↑ Fleenor, M.E.; Harden, J.W.; Curtis, G. «Interaction between carbamazepine and antituberculosis agents». Chest, vol. 99, 6, 6-1991, pàg. 1554. DOI: 10.1378/chest.99.6.1554a. PMID: 2036861.

- ↑ Baciewicz, A.M.; Baciewicz Jr., F.A. «Ketoconazole and fluconazole drug interactions». Archives of Internal Medicine, vol. 153, 17, 13-09-1993, pàg. 1970–1976. DOI: 10.1001/archinte.153.17.1970. PMID: 8357281.

- ↑ 34,0 34,1 Jonville, A.P.; Gauchez, A.S.; Autret, E.; Billard, C.; Barbier, P.; Nsabiyumva, F.; Breteau, M. «Interaction between isoniazid and valproate: a case of valproate overdosage». European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 40, 2, 1991, pàg. 197–198. DOI: 10.1007/BF00280078. PMID: 2065702.

- ↑ Bass, Jr., J.B.; Farer, L.S.; Hopewell, P.C.; O'Brien, R.; Jacobs, R.F.; Ruben, F.; Snider, Jr., D.E.; Thornton, G. «Treatment of tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in adults and children. American Thoracic Society and The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention». Am J Respir Crit Care Med, vol. 149, 5, 5-1994, pàg. 1359–1374. DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.5.8173779. PMID: 8173779.

- ↑ Höglund, P.; Nilsson, L.G.; Paulsen, O. «Interaction between isoniazid and theophylline». European Journal of Respiratory Diseases, vol. 70, 2, 2-1987, pàg. 110–116. PMID: 3817069.

- ↑ Suarez, J.; Ranguelova, K.; Jarzecki, A.A. «An oxyferrous heme/protein-based radical intermediate is catalytically competent in the catalase reaction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis catalase-peroxidase (KatG)». The Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 284, 11, 3-2009, pàg. 7017–7029. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M808106200. PMC: 2652337. PMID: 19139099.

- ↑ Timmins, G.S.; Master, S; Rusnak, F.; Deretic, V. «Nitric oxide generated from isoniazid activation by KatG: source of nitric oxide and activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis». Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, vol. 48, 8, 8-2004, pàg. 3006–3009. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3006-3009.2004. PMC: 478481. PMID: 15273113.

- ↑ Singh, R.; Manjunatha, U.; Boshoff, H.I. «PA-824 kills nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis by intracellular NO release». Science, vol. 322, 5906, 11-2008, pàg. 1392–1395. Bibcode: 2008Sci...322.1392S. DOI: 10.1126/science.1164571. PMC: 2723733. PMID: 19039139.

- ↑ Ahmad, Z.; Klinkenberg, L.G.; Pinn, M.L.; Fraig, M.M.; Peloquin, C.A.; Bishai, W.R.; Nuermberger, E.L.; Grosset, J.H.; Karakousis, P.C. «Biphasic Kill Curve of Isoniazid Reveals the Presence of Drug‐Tolerant, Not Drug‐Resistant, Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Guinea Pig». The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 200, 7, 2009, pàg. 1136–1143. DOI: 10.1086/605605. PMID: 19686043.

- ↑ Harvey, Richard A.; Howland, Richard D.; Mycek, Mary Julia [et al.].. Pharmacology. 864. 4th. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006. ISBN 9780781741187.

- ↑ Judd, F. K.; Mijch, A. M.; Cockram, A.; Norman, T. R. «Isoniazid and antidepressants: is there cause for concern?». International Clinical Psychopharmacology, vol. 9, 2, 1994, pàg. 123–125. DOI: 10.1097/00004850-199400920-00009. ISSN: 0268-1315. PMID: 8056994.

- ↑ Riede, Hans L. «Fourth-generation fluoroquinolones in tuberculosis». Lancet, vol. 373, 9670, 2009, pàg. 1148–1149. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60559-6. PMID: 19345815.

- ↑ «History». rocheusa.com. Roche USA. Arxivat de l'original el 2007-12-12.

- ↑ Jones, David S. «The Health Care Experiments at Many Farms: The Navajo, Tuberculosis, and the Limits of Modern Medicine, 1952–1962». Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 76, 4, 2002, pàg. 749–790. DOI: 10.1353/bhm.2002.0186. PMID: 12446978.

- ↑ Beeson, Paul B. «Walsh McDermott». A: Biographical Memoirs: V.59. National Academies Press, 1990, p. 282–307.

- ↑ Moncrieff, Joanna «The creation of the concept of an antidepressant: an historical analysis». Social Science & Medicine, vol. 66, 11, 6-2008, pàg. 2346–2355. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.047. ISSN: 0277-9536. PMID: 18321627.

- ↑ William Andrew Publishing. Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia. 3rd. Norwich, NY: Elsevier Science, 2008, p. 1968–1970. ISBN 9780815515265.

- ↑ Baizer, Manuel M.; Dub, Michael; Gister, Sidney; Steinberg, Nathan G. «Synthesis of Isoniazid from Citric Acid». Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association (Scientific Ed.), vol. 45, 7, 1956, pàg. 478–480. DOI: 10.1002/jps.3030450714. ISSN: 0095-9553. PMID: 13345683.

- ↑ «Drugs@FDA». fda.gov. United States Food and Drug Administration. Arxivat de l'original el 14 August 2012. [Consulta: 22 agost 2016].

- ↑ Smith, L.L.; Foell, Theodore «Differentiation of Δ4-3-Ketosteroids and Δ1,4-3-Ketosteroids with Isonicotinic Acid Hydrazide». Analytical Chemistry, vol. 31, 1, 1959, pàg. 102–105. DOI: 10.1021/ac60145a020.

- ↑ Sykes, Jane E. Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases (E-Book). Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013, p. 425. ISBN 978-0323241946.

Further reading

[modifica]- «Isoniazid overdose: recognition and management». Am Fam Physician, vol. 57, 4, 2-1998, pàg. 749–52. PMID: 9490997.

External links

[modifica]- «Isoniazid». Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.