Usuari Discussió:Pere Serafi/constitució

|

|

Aquest article o secció s'està traduint a partir de: «Constitution» (anglès), amb llicència CC-BY-SA Hi pot haver llacunes de contingut, errors sintàctics o escrits sense traduir. |

History and development

[modifica]Història i desenvolupament

[modifica]Early constitutions

[modifica]Primeres constitucions

[modifica]Excavations in modern-day Iraq by Ernest de Sarzec in 1877 found evidence of the earliest known code of justice, issued by the Sumerian king Urukagina of Lagash ca 2300 BC. Perhaps the earliest prototype for a law of government, this document itself has not yet been discovered; however it is known that it allowed some rights to his citizens. For example, it is known that it relieved tax for widows and orphans, and protected the poor from the usury of the rich.

Excavacions en dia modern Iraq per Ernest De Sarzec el 1877 trobava evidència del primer codi conegut de justícia, emès pel rei Sumeri Urukagina de Lagash circa 2300 Bc. Potser el primer prototip per a una llei de govern, aquest document mateix no s'ha descobert encara; tanmateix se sap que permetia alguns drets als seus ciutadans. Per exemple, se sap que alleugeria impost per a vídues i orfes, i protegia els pobres de la usura dels rics.

After that, many governments ruled by special codes of written laws. The oldest such document still known to exist seems to be the Code of Ur-Nammu of Ur (ca 2050 BC). Some of the better-known ancient law codes include the code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin, the code of Hammurabi of Babylonia, the Hittite code, the Assyrian code and Mosaic law.

After that, many governments ruled by special codes of written laws. The oldest such document still known to exist seems to be the Code of Ur-Nammu of Ur (ca 2050 BC). Some of the better-known ancient law codes include the code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin, the code of Hammurabi of Babylonia, the Hittite code, the Assyrian code and Mosaic law.

Després d'allò, molts governs dominats per codis especials de drets escrits. El tal document més vell del qual encara se sàpiga que existeix sembla que sigui el Codi Of Ur-nammu de Ur ( circa 2050 Bc). Alguns dels codis de llei antics més coneguts inclouen el codi de Lipit-ishtar d'Isin, el Codi of hammurabi de Babilònia, el Codi hittite, el Codi d'assiri i Llei de mosaic.

Later constitutions

[modifica]=== constitutions=== Posterior

Athens

[modifica]Atenes

[modifica]In 621 BC a scribe named Draco codified the cruel oral laws of the city-state of Athens; this code prescribed the death penalty for many offences (nowadays very severe rules are often called "Draconian"). In 594 BC Solon, the ruler of Athens, created the new Solonian Constitution. It eased the burden of the workers, and determined that membership of the ruling class was to be based on wealth (plutocracy), rather than by birth (aristocracy). Cleisthenes again reformed the Athenian constitution and set it on a democratic footing in 508 BC.

En 621 Bc un escribà anomenat Draco codificava els drets orals cruels de l'estat de Ciutat d'Atenes; aquest codi prescrivia la pena de mort per molts delictes (avui dia les regles molt severes s'anomenen sovint "Draco (lawgiver)#"draconian"|draconian"). En 594 Bc Solon, el governant d'Atenes, creava el nou SOLONIAN CONSTITUTION . Alleujava la càrrega dels treballadors, i determinava que l'afiliació de la classe dirigent s'hagués de basar en riquesa (PLUTOCRACY), força que per naixement (ARISTOCRÀCIA). Cleisthenes una altra vegada reformava la constitució Athenian i el posa sobre una posició democràtica en 508 Bc.

Aristotle (ca 350 BC) was one of the first in recorded history to make a formal distinction between ordinary law and constitutional law, establishing ideas of constitution and constitutionalism, and attempting to classify different forms of constitutional government. The most basic definition he used to describe a constitution in general terms was "the arrangement of the offices in a state". In his works Constitution of Athens, Politics, and Nicomachean Ethics he explores different constitutions of his day, including those of Athens, Sparta, and Carthage. He classified both what he regarded as good and what he regarded as bad constitutions, and came to the conclusion that the best constitution was a mixed system, including monarchic, aristocratic, and democratic elements. He also distinguished between citizens, who had the right to participate in the state, and non-citizens and slaves, who did not.

Aristotle ( circa 350 Bc) era un dels primers en la història enregistrada per fer una distinció formal entre llei corrent i dret constitucional, establint idees de constitució i constitucionalisme, i intentant classificar formes diferents de govern constitucional. La definició més bàsica que solia descriure a una constitució en termes generals era "l'arranjament de les oficines en un estat". En els seus treballs Constitució D'atenes, Política, i Nicomachean Ethics explora constitucions diferents del seu dia, incloent-hi aquells d'Atenes, Sparta, i Carthage. En classificava tant el que veia com bo com el que considerava com males constitucions, i arribava a la conclusió que la millor constitució era un sistema mixt, incloent-hi elements monàrquics, aristocràtics, i democràtics. També distingia entre ciutadans, que tenien el dret de participar en l'estat, i no-ciutadans i esclaus, que feia no.

Rome

[modifica]Roma

[modifica]The Romans first codified their constitution in 450 BC as the Twelve Tables. They operated under a series of laws that were added from time to time, but Roman law was never reorganised into a single code until the Codex Theodosianus (AD 438); later, in the Eastern Empire the Codex repetitæ prælectionis (534) was highly influential throughout Europe. This was followed in the east by the Ecloga of Leo III the Isaurian (740) and the Basilica of Basil I (878).

Els romans primer codificaven la seva constitució en 450 Bc com el Dotze Taules . Operaven sota una sèrie de drets que s'afegien de tant en tant, però Llei romana era mai no reorganitzat a un codi únic fins al Codex Theodosianus (Anunci 438); més tard, en l'Imperi Oriental el codex repetitæ PRÆLectionis (534) era altament influent per tota Europa. Això se seguia a l'est pel Ecloga de Leo Iii L'isaurian (740) i el Basílica de BASIL jo (878).

India

[modifica]Índia

[modifica]The Edicts of Ashoka established constitutional principles for the 3rd century BC Maurya king's rule in Ancient India.

El Edicts Of Ashoka principis constitucionals establerts per a la regla del 3r rei Bc Maurya de segle a índia Antiga.

Germania

[modifica]Germània

[modifica]Many of the Germanic peoples that filled the power vacuum left by the Western Roman Empire in the Early Middle Ages codified their laws. One of the first of these Germanic law codes to be written was the Visigothic Code of Euric (471). This was followed by the Lex Burgundionum, applying separate codes for Germans and for Romans; the Pactus Alamannorum; and the Salic Law of the Franks, all written soon after 500. In 506, the Breviarum or "Lex Romana" of Alaric II, king of the Visigoths, adopted and consolidated the Codex Theodosianus together with assorted earlier Roman laws. Systems that appeared somewhat later include the Edictum Rothari of the Lombards (643), the Lex Visigothorum (654), the Lex Alamannorum (730) and the Lex Frisionum (ca 785). These continental codes were all composed in Latin, whilst Anglo-Saxon was used for those of England, beginning with the Code of Ethelbert of Kent (602). In ca. 893, Alfred the Great combined this and two other earlier Saxon codes, with various Mosaic and Christian precepts, to produce the Doom Book code of laws for England.

Moltes de les poblacions Germàniques que omplien el buit de poder deixat per l'Imperi romà Occidental en la Primera Edat Mitjana codificaven els seus drets. Un dels primers d'aquests Codis de llei GermÀNics per ser escrits era el Visigothic Codi d'Euric (471). Això se seguia pel Lex Burgundionum, aplicant codis separats per a alemanys i per a romans; el Pactus Alamannorum; i la Llei Salic del Franqueja, completament escrit aviat després de 500. En 506, el Breviarum o "Lex Romana" d'Alaric Ii, rei dels visigots, adoptats i consolidats el Codex Theodosianus juntament amb drets romans anteriors assortits. Els sistemes que semblaven una mica posteriors inclouen el Edictum Rothari dels Llombards (643), el Lex Visigothorum (654), el Lex Alamannorum (730) i el Lex Frisionum ( circa 785). Aquests codis continentals tot es componien en llatí, mentre Anglosaxó era utilitzat per als d'Anglaterra, començant amb el Codi d'ETHELBERT OF KENT (602). En circa. 893, ALFRED THE GREAT combinava això i dos altres codis de saxó anteriors, amb diversos Mosaic i mandats judicials cristians, produir el ''llibre de perdició'' codi de drets per a Anglaterra.

Japan

[modifica]Japó

[modifica]Japan's Seventeen-article constitution written in 604, reportedly by Prince Shōtoku, is an early example of a constitution in Asian political history. Influenced by Buddhist teachings, the document focuses more on social morality than institutions of government per se and remains a notable early attempt at a government constitution.

Japó ConstituciÓ de Disset Article escrit en 604, segons hom diu per Prince SHTOKU, és un primer exemple d'una constitució en la història política asiàtica. Influït per ensenyaments BUDISTES, el document se centra més en moral social que les institucions de govern per se i roman un primer intent notable d'una constitució governamental.

Medina

[modifica]Medina

[modifica]The Constitution of Medina (àrab: صحیفة المدینه, Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīna), also known as the Charter of Medina, was drafted by the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It constituted a formal agreement between Muhammad and all of the significant tribes and families of Yathrib (later known as Medina), including Muslims, Jews, and pagans.[1][2] The document was drawn up with the explicit concern of bringing to an end the bitter inter tribal fighting between the clans of the Aws (Aus) and Khazraj within Medina. To this effect it instituted a number of rights and responsibilities for the Muslim, Jewish, and pagan communities of Medina bringing them within the fold of one community—the Ummah.[3]

La Constitució De Medina (صحیفة المدینه, afat al-Madna), també conegut com la Carta de Medina, era reclutat pel Prophet Muhammad IslÀMIC. Constituïa un acord formal entre Muhammad i tot les tribus significatives i famílies de Yathrib (més tard conegut com MEDINA), incloent-hi Musulmans, Jueus, i pagans.[4].[5]. El document es redactava amb la preocupació explícita de portar a un final dins del qual els amargs enterren baralla tribal entre els clans de l'Aws (aus) i Khazraj Medina. A aquest efecte instituïa un cert nombre de drets i responsabilitats pel musulmà, comunitats jueves, i paganes de Medina que els portaven dins del plec d'un Ummah comunitat el.[6].

The precise dating of the Constitution of Medina remains debated but generally scholars agree it was written shortly after the Hijra (622).[7] It effectively established the first Islamic state. The Constitution established: the security of the community, religious freedoms, the role of Medina as a haram or sacred place (barring all violence and weapons), the security of women, stable tribal relations within Medina, a tax system for supporting the community in time of conflict, parameters for exogenous political alliances, a system for granting protection of individuals, a judicial system for resolving disputes, and also regulated the paying of Blood money (the payment between families or tribes for the slaying of an individual in lieu of lex talionis).

La datació precisa de la Constitució de Medina roman discutida però generalment els becaris accepten era escrit en breu després de l'Hijra (622).[8]. Eficaçment establia el primer estat islàmic. La Constitució establerta: la seguretat de la comunitat, llibertats religioses, el paper de Medina com un haram o lloc sagrat (barrant tota la violència i armes), la seguretat de dones, relacions tribals estables dins de Medina, un sistema fiscal per donar suport a la comunitat a temps de conflicte, paràmetres per a aliances polítiques exògenes, un sistema per concedir protecció d'individus, un sistema judicial per a disputes que resolen, i també ser regulat el pagar de Diners de sang (el pagament entre famílies o tribus per al matar d'un individu en lloc de lex talionis).

Wales

[modifica]País de Gal·les

[modifica]In Wales, the Cyfraith Hywel was codified by Hywel Dda c. 942–950.

A País de gal·les, el ''cyfraith hywel'' era codificat per c de Hywel Dda. 942-950.

Rus

[modifica]Rus

[modifica]The Pravda Yaroslava, originally combined by Yaroslav the Wise the Grand Prince of Kiev, was granted to Great Novgorod around 1017, and in 1054 was incorporated into the Russkaya Pravda, that became the law for all of Kievan Rus. It survived only in later editions of the 15th century.

El Pravda Yaroslava, originalment combinat per Yaroslav The Wise el Gran Príncep De Kíev, era admès que a Great Novgorod al voltant de 1017, i dins s'incorporava a 1054 el Russkaya Pravda, que es convertia en la llei per a tot de Kievan Rus. Sobrevivia només en edicions posteriors del 15è segle.

Iroquois

[modifica]Iroquois

[modifica]The Gayanashagowa, the oral constitution of the Iroquois nation also known as the Great Law of Peace, established a system of governance in which sachems (tribal chiefs) of the members of the Iroquois League made decisions on the basis of universal consensus of all chiefs following discussions that were initiated by a single tribe. The position of sachem descended through families, and were allocated by senior female relatives.[9]

El Gayanashagowa, la constitució oral de la nació d'Iroquois també conegut com la Gran Llei de Pau, establia un sistema de govern en quin sachems (caps tribals) dels membres de l'Iroquois que League prenia decisions sobre la base de consens universal de tots els caps després de discussions que eren iniciades per una tribu única. La posició de sachem baixava a través de famílies, i era assignada per parents femenins superiors.[9].

Historians including Donald Grindle,[10] Bruce Johansen[11] and others[12] believe that the Iroquois constitution provided inspiration for the United States Constitution and in 1988 was recognised by a resolution in Congress.[13] The thesis is not considered credible.[9][14] Stanford University historian Jack N. Rakove stated that "The voluminous records we have for the constitutional debates of the late 1780s contain no significant references to the Iroquois" and stated that there are ample European precedents to the democratic institutions of the United States.[15] Francis Jennings noted that the statement made by Benjamin Franklin frequently quoted by proponents of the thesis does not support for this idea as it is advocating for a union against these "ignorant savages" and called the idea "absurd".[16] Anthropologist Dean Snow stated that though Franklin's Albany Plan may have drawn some inspiration from the Iroquois League, there is little evidence that either the Plan or the Constitution drew substantially from this source and argues that "...such claims muddle and denigrate the subtle and remarkable features of Iroquois government. The two forms of government are distinctive and individually remarkable in conception."[17]

Historiadors incloent-hi Donald Grindle,[18]. Bruce Johansen [19]. i altres [12]. creure que la constitució Iroquois proporcionava inspiració per la Constitució dels Estats Units i el 1988 era reconeguda per una resolució en Congrés.[20]. La tesi no es considera creïble.[9][14]. historiador de Stanford University Jack N. Rakove a qui es manifesta que "Els registres voluminosos que tenim per als debats constitucionals dels últims anys 1780 no contenen referències significatives a l'Iroquois" i a qui es manifesta que hi ha precedents europeus suficients a les institucions democràtiques dels Estats Units.[21]. Francis Jennings es fixava que la declaració feta per Benjamin Franklin freqüentment citat per defensors de la tesi fa no donar suport per a aquesta idea com està defensant per a una unió contra aquests "salvatges ignorants" i anomenava la idea "absurd".[22]. Neu de Degà d'Antropòleg a què es manifesta que encara que Franklin ALBANY PLAN pot haver tret una mica d'inspiració de l'Iroquois League, hi ha poca evidència que o el Pla o la Constitució dibuixava substancialment des d'aquesta font i discuteix aquell "... tals reclamacions confonen i denigrar els trets subtils i notables de govern Iroquois. Les dues formes de govern són distintives i individualment notables en la concepció." [23].

England

[modifica]Anglaterra

[modifica]In England, Henry I's proclamation of the Charter of Liberties in 1100 bound the king for the first time in his treatment of the clergy and the nobility. This idea was extended and refined by the English barony when they forced King John to sign Magna Carta in 1215. The most important single article of the Magna Carta, related to "habeas corpus", provided that the king was not permitted to imprison, outlaw, exile or kill anyone at a whim—there must be due process of law first. This article, Article 39, of the Magna Carta read:

A Anglaterra, Henri jo és proclamació de la Carta Of Liberties el 1100 lligava el rei per primera vegada en el seu tractament del clergat i la noblesa. Aquesta idea s'estenia i era refinada per la baronia anglesa quan forçaven King John a signar Magna Carta el 1215. L'article únic més important del Magna Carta, es referia a " habeas corpus ", a condició que al rei no se li permetés empresonar, proscriure, exilar o matar-ne qualsevol a un caprici allà ha de ser procés degut de llei primer. Aquest article, Article 39, del Magna Carta lectura:

No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.

Cap home lliure no s'arrestarà, o empresonava, o privava de la seva propietat, o proscrivia, o exilava, o de qualsevol manera destruïa, ni ens n'anirem contra ell o enviarem contra ell, llevat que per judici legal dels seus iguals, o prop de la llei de la terra.

This provision became the cornerstone of English liberty after that point. The social contract in the original case was between the king and the nobility, but was gradually extended to all of the people. It led to the system of Constitutional Monarchy, with further reforms shifting the balance of power from the monarchy and nobility to the House of Commons.

Aquesta provisió es convertia en la pedra angular de llibertat anglesa després d'aquell punt. El contracte social en el cas original era entre el rei i la noblesa, però s'estenia gradualment a totes les gents. Conduïa al sistema de Monarquia Constitucional, amb altres reformes que canviaven l'equilibri de poder de la monarquia i noblesa a l'House Of Commons.

Serbia

[modifica]Serbia

[modifica]The Nomocanon of Saint Sava (serbi: Zakonopravilo)[24][25][26] was the first Serbian constitution from 1219. This legal act was well developed. St. Sava's Nomocanon was the compilation of Civil law, based on Roman Law and Canon law, based on Ecumenical Councils and its basic purpose was to organize functioning of the young Serbian kingdom and the Serbian church. Saint Sava began the work on the Serbian Nomocanon in 1208 while being at Mount Athos, using The Nomocanon in Fourteen Titles, Synopsis of Stefan the Efesian, Nomocanon of John Scholasticus, Ecumenical Councils' documents, which he modified with the canonical commentaries of Aristinos and John Zonaras, local church meetings, rules of the Holy Fathers, the law of Moses, translation of Prohiron and the Byzantine emperors' Novellae (most were taken from Justinian's Novellae). The Nomocanon was completely new compilation of civil and canonical regulations, taken from the Byzantine sources, but completed and reformed by St. Sava to function properly in Serbia. Beside decrees that organized the life of church, there are various norms regarding civil life, most of them were taken from Prohiron. Legal transplants of Roman-Byzantine law became the basis of the Serbian medieval law. The essence of Zakonopravilo was based on Corpus Iuris Civilis.

El Nomocanon de Saint Sava (serbi: Zakonopravilo) [27].[28].[29]. era la primera constitució de Serbi des de 1219. Aquest acte legal es desenvolupava bé. El Nomocanon De Sava De C. era la compilació de Dret civil, basat en Llei Romana i Dret canònic, basada en Consells Ecumenical i el seu propòsit bàsic havia d'organitzar funcionament del Regne de serbi jove i l'Església de serbi. Saint Sava començava el treball en el serbi Nomocanon el 1208 mentre era al Mont Athos, utilitzant El Nomocanon en Catorze Títols, Sumari de Stefan l'Efesian, Nomocanon de John Scholasticus, els documents de Consells Ecumenical, que modificava amb els canònics comentaris d'Aristinos i John Zonaras, reunions d'església locals, regles dels Pares Sagrats, la llei de Moses, traducció de Prohiron i el Novellae dels Emperadors romans d'Orient (molts s'agafaven de Justinian Novellae). El Nomocanon era compilació completament nova de civils i canòniques regulacions, preses de les fonts Bizantines, però completades i reformades per c. Sava per funcionar pròpiament a Serbia. Al costat de decrets que organitzaven la vida d'església, hi ha diverses normes quant a vida civil, la majoria d'ells es prenien de Prohiron. Les Trasplantacions legals de Roman-byzantine Law es convertien en la base de la llei medieval de serbi. L'essència de Zakonopravilo es basava en CORPUS IURIS CIVILIS.

Stefan Dušan, Emperor of Serbs and Greeks, enacted Dušan's Code (serbi: Dušanov Zakonik)[30] in Serbia, in two state congresses: in 1349 in Skopje and in 1354 in Serres. It regulated all social spheres, so it was the second Serbian constitution, after St. Sava's Nomocanon (Zakonopravilo). The Code was based on Roman-Byzantine law. The legal transplanting is notable with the articles 171 and 172 of Dušan's Code, which regulated the juridical independence. They were taken from the Byzantine code Basilika (book VII, 1, 16-17).

Stefan Du An, Emperador de Serbs i grecs, promulgava El Codi De Du An (serbi: Dušanov Zakonik) [31]. a Serbia, en dos congressos estatals: el 1349 a Skopje i el 1354 en Serres. Regulava totes les esferes socials, així era la segona constitució de serbi, després de St. el Nomocanon de Sava (Zakonopravilo). El Codi es basava en Roman-byzantine Law. eL trasplantar legal és notable amb els articles 171 i 172 del Codi de Dusan, que regulava la independència jurídica. S'agafaven del Basilika de codi romà d'Orient (llibre Vii, 1, 16-17).

Hungary

[modifica]Hongria

[modifica]In 1222, Hungarian King Andrew II issued the Golden Bull of 1222.

El 1222, el Rei hongarès Andrew Ii emetia el Brau Daurat De 1222.

Saxony

[modifica]Saxony

[modifica]Between 1220 and 1230, a Saxon administrator, Eike von Repgow, composed the Sachsenspiegel, which became the supreme law used in parts of Germany as late as 1900.

Entre 1220 i 1230, un administrador Saxó, Eike Von Repgow, compost el Sachsenspiegel, que es convertia en la llei suprema utilitzada en parts de tan últim com 1900 Alemanya.

Mali Empire

[modifica]Imperi de Mali

[modifica]In 1236, Sundiata Keita presented an oral constitution federating the Mali Empire, called the Kouroukan Fouga.

El 1236, Sundiata Keita presentava una constitució oral que federating l'Imperi De Mali, anomenava el Kouroukan Fouga .

Ethiopia

[modifica]Etiòpia

[modifica]Meanwhile, around 1240, the Coptic Egyptian Christian writer, 'Abul Fada'il Ibn al-'Assal, wrote the Fetha Negest in Arabic. 'Ibn al-Assal took his laws partly from apostolic writings and Mosaic law, and partly from the former Byzantine codes. There are a few historical records claiming that this law code was translated into Ge'ez and entered Ethiopia around 1450 in the reign of Zara Yaqob. Even so, its first recorded use in the function of a constitution (supreme law of the land) is with Sarsa Dengel beginning in 1563. The Fetha Negest remained the supreme law in Ethiopia until 1931, when a modern-style Constitution was first granted by Emperor Haile Selassie I.

Mentrestant, al voltant de 1240, el Copte escriptor cristià egipci, 'abul Fada'il Ibn Al-'assal, escrivia el Fetha Negest en àrab. 'Ibn al-Assal prenia els seus drets en part d'escriptures apostòliques i llei de Mosaic, i en part dels anteriors codis romans d'Orient. Hi ha uns quants registres històrics que afirmen que aquest codi de llei es traduïa a Ge'ez i Etiòpia a què s'ingressava al voltant de 1450 en el regnat de Zara Yaqob. Tot i així, el seu primer ús enregistrat en la funció d'una constitució (llei suprema de la terra) és amb començament de Sarsa Dengel el 1563. El Fetha Negest romàs la llei suprema a Etiòpia fins a 1931, quan una Constitució d'estil modern era primer concedida per Emperor Haile Selassie I.

China

[modifica]Xina

[modifica]In China, the Hongwu Emperor created and refined a document he called Ancestral Injunctions (first published in 1375, revised twice more before his death in 1398). These rules served in a very real sense as a constitution for the Ming Dynasty for the next 250 years.

A la Xina, l'Emperador D'hongwu creava i refinava un document que cridava Ancestrals Requeriments (primer publicat el 1375, revisat dues vegades més abans de la seva mort el 1398). Aquestes regles servien de veritat com a constitució per a la Dinastia De Ming durant els 250 propers anys.

Sardinia

[modifica]Sardenya

[modifica]In 1392 the Carta de Logu was legal code of the Giudicato of Arborea promulgated by the giudicessa Eleanor. It was in force in Sardinia until it was superseded by the code of Charles Felix in April 1827. The Carta was a work of great importance in Sardinian history. It was an organic, coherent, and systematic work of legislation encompassing the civil and penal law.

El 1392 el Carta de Logu era codi legal del Giudicato Of Arborea promulgat pel giudicessa Eleanor. Estava en vigor a Sardenya fins que era substituït pel codi de Charles Felix l'abril de 1827. El Carta era un treball de gran importància en la història de Sard. Era un treball orgànic, coherent, i sistemàtic de legislació que incloïa la civil i penal llei.

Modern constitutions

[modifica]=== constitutions=== Modern

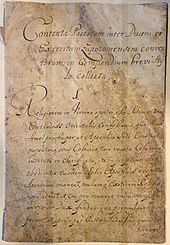

The earliest written constitution still governing a sovereign nation today may be that of San Marino. The Leges Statutae Republicae Sancti Marini was written in Latin and consists of six books. The first book, with 62 articles, establishes councils, courts, various executive officers and the powers assigned to them. The remaining books cover criminal and civil law, judicial procedures and remedies. Written in 1600, the document was based upon the Statuti Comunali (Town Statute) of 1300, itself influenced by the Codex Justinianus, and it remains in force today.

La primera constitució escrita que encara governa una nació de sobirans avui pot ser allò de San Marino. El Leges Statutae Republicae Sancti Marini era escrit en llatí i consta de sis llibres. El primer llibre, amb 62 articles, estableix consells, jutjats, diversos oficials executius i els poders assignats a ells. Els llibres restants cobreixen llei criminal i civil, procediments judicials i remeis. Escrit en 1600, el document es basava al Statuti Comunali (Estatut de Ciutat) de 1300, això mateix influït pel Codex Justinianus, i roman en vigor avui.

In 1639, the Colony of Connecticut adopted the Fundamental Orders, which is considered the first North American constitution, and is the basis for every new Connecticut constitution since, and is also the reason for Connecticut's nickname, "the Constitution State". England had two short-lived written Constitutions during Cromwellian rule, known as the Instrument of Government (1653), and Humble Petition and Advice (1657).

El 1639, la ColÒNia Of Connecticut adoptava les Ordres Fonamentals, la qual cosa es considera la primera constitució Americana Nord, i és la base per cada constitució de Connecticut nova de llavors ençà, i és també la raó per al renom de Connecticut, "l'ESTAT DE CONSTITUCIÓ". Anglaterra tenia dues Constitucions escrites passatgeres durant regla Cromwellian, coneguda com l'Instrument De Govern (1653), i PETICIÓ HUMIL I CONSELL (1657).

Agreements and Constitutions of Laws and Freedoms of the Zaporizian Host can be acknowledged as the first European constitution in a modern sense.[32] It was written in 1710 by Pylyp Orlyk, hetman of the Zaporozhian Host. This "Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk" (as it is widely known) was written to establish a free Zaporozhian-Ukrainian Republic, with the support of Charles XII of Sweden. It is notable in that it established a democratic standard for the separation of powers in government between the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches, well before the publication of Montesquieu's Spirit of the Laws. This Constitution also limited the executive authority of the hetman, and established a democratically elected Cossack parliament called the General Council. However, Orlyk's project for an independent Ukrainian State never materialized, and his constitution, written in exile, never went into effect.

Ofereixen Els Acords I Les Constitucions De Laws And Freedoms Of The Zaporizian pot ser admès com la primera constitució europea en un sentit modern.[33]. Era escrit en 1710 per Pylyp Orlyk, hetman de l'AmfitriÓ DE ZAPOROZHIAN. Això "CONSTITUCIÓ DE PYLYP ORLYK" (com se sap àmpliament) era escrit establir un Zaporozhian-Ukrainian Republic lliure, amb el suport de Charles Xii De Suècia. És notable ja que establia que es bifurca un estàndard democràtic per a la separació de poders en govern entre el legislatiu, executiu, i magistratura, bé abans de la publicació de Montesquieu Esperit Dels Drets . Aquesta Constitució també limitava l'autoritat executiva del hetman, i establia que un parlament de cosac democràticament elegit anomenava el Consell General. Tanmateix, el projecte d'Orlyk per a un Ucraïnès Estat independent mai no es materialitzava, i la seva constitució, escrita en exili, mai no entrava a efecte.

Other examples of early European constitutions were the Corsican Constitution of 1755 and the Swedish Constitution of 1772.

Uns altres exemples de primeres constitucions europees eren la Constitució De Cors de 1755 i la Constitució Sueca De 1772.

All of the British colonies in North America that were to become the 13 original United States, adopted their own constitutions in 1776 and 1777, during the American Revolution (and before the later Articles of Confederation and United States Constitution), with the exceptions of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts adopted its Constitution in 1780, the oldest still-functioning constitution of any U.S. state; while Connecticut and Rhode Island officially continued to operate under their old colonial charters, until they adopted their first state constitutions in 1818 and 1843, respectively.

Totes les colònies britàniques a Amèrica del Nord que s'havien de convertir en l'original de 13 Estats Units, adoptaven les seves pròpies constitucions en 1776 i 1777, durant la Revolució americana (i abans dels Articles posteriors De ConfederaciÓ i ConstituciÓ DELS ESTATS UNITS), amb les excepcions de Massachusetts, Illa de Connecticut i Rhode. La COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS adoptava la seva Constitució el 1780, la constitució de funcionament quiet més vella de qualsevol estat dels EUA; mentre Connecticut i Rhode Island oficialment continuaven operant sota les seves cartes colonials velles, fins que adoptaven les seves primeres constitucions estatals el 1818 i el 1843, respectivament.

Enlightenment constitutions

[modifica]constitucions d'Il·luminació

[modifica]What is sometimes called the "enlightened constitution" model was developed by philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment such as Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Locke. The model proposed that constitutional governments should be stable, adaptable, accountable, open and should represent the people (i.e. support democracy).[34]

Què és a vegades anomenat el "constitució instruïda" model era desenvolupat per filòsofs de l'Edat D'il·luminació com Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, i John Locke. El model proposava que els governs constitucionals haurien de ser estables, adaptable, responsable, obre i hauria de representar la gent (i.e. democràcia de suport).[35].

The United States Constitution, ratified June 21, 1788, was influenced by the British constitutional system and the political system of the United Provinces, plus the writings of Polybius, Locke, Montesquieu, and others. The document became a benchmark for republicanism and codified constitutions written thereafter.

La Constitució dels Estats Units, ratificat 21 de juny, de 1788, era influïda pel sistema constitucional britànic i el sistema polític de les Províncies Unides, més les escriptures de Polybius, Locke, Montesquieu, i altres. El document es convertia en un punt de referència per al republicanisme i codificava constitucions escrites després.

Next were the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Constitution of May 3, 1791,[36][37][38] and the French Constitution of September 3, 1791.

Després era la ConstituciÓ DE Commonwealth Polonesa Lituana De 3 De Maig, De 1791,[39].[40].[38]. i la CONSTITUCIÓ FRANCESA DE 3 DE SETEMBRE, DE 1791.

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 served as a model for other liberal constitutions of several South-European and Latin American nations like Portuguese Constitution of 1822, constitutions of various Italian states during Carbonari revolts (i.e. in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies), or Mexican Constitution of 1824.[41] As a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the absolute monarchy of Denmark lost its personal possession of Norway to another absolute monarchy, Sweden. However the Norwegians managed to infuse a radically democratic and liberal constitution in 1814, adopting many facets from the American constitution and the revolutionary French ones; but maintaining a hereditary monarch limited by the constitution, like the Spanish one. The Serbian revolution initially led to a proclamation of a proto-constitution in 1811; the full-fledged Constitution of Serbia followed few decades later, in 1835.

La Constitució Espanyola De 1812 servia com a model perquè a unes altres constitucions liberals d'unes quantes nacions Cap Al Sud Europees i Llatinoamericanes els agraden LA Constitució Portuguesa De 1822, les constitucions de diversos estats ITALIANS durant rebel·lions de Carbonari (i.e. al REGNE OF THE TWO SICILIES), o LA Constitució Mexicana De 1824.[42]. Com a resultat de les Guerres Napoleòniques, la monarquia absoluta de Dinamarca perdia la seva possessió personal de Noruega a una altra monarquia absoluta, Suècia. Tanmateix, els noruecs aconseguien fer una infusió d'una constitució radicalment democràtica i liberal el 1814, adoptant moltes facetes de la constitució americana i els revolucionaris francesos; però mantenint un monarca hereditari limitat per la constitució, agradi l'espanyol. La Revolució de serbi inicialment conduïa a una proclamació d'una protoconstitució el 1811; la Constitució de ple dret de Serbia seguia poques dècades més tard, el 1835.

Principles of constitutional design

[modifica]Principis de disseny constitucional

[modifica]After tribal people first began to live in cities and establish nations, many of these functioned according to unwritten customs, while some developed autocratic, even tyrannical monarchs, who ruled by decree, or mere personal whim. Such rule led some thinkers to take the position that what mattered was not the design of governmental institutions and operations, as much as the character of the rulers. This view can be seen in Plato, who called for rule by "philosopher-kings."[43] Later writers, such as Aristotle, Cicero and Plutarch, would examine designs for government from a legal and historical standpoint.

Després que la gent tribal primer comencés a viure en ciutats i establir nacions, molts d'aquests funcionaven segons duana oral, mentre alguns es desenvolupaven autocràtic, monarques fins i tot tirànics, que governava per decret, o mer caprici personal. Tal regla portada alguns pensadors per prendre la posició que el que importava no era el disseny d'institucions governamentals i operacions, tant com el caràcter dels governants. Aquesta vista es pot veure en Plato, que anomenava per a la regla per reis "de filòsof." [44]. escriptors Posteriors, com Aristotle, Cicero i Plutarch, examinaria dissenys per a govern d'un punt de vista legal i històric.

The Renaissance brought a series of political philosophers who wrote implied criticisms of the practices of monarchs and sought to identify principles of constitutional design that would be likely to yield more effective and just governance from their viewpoints. This began with revival of the Roman law of nations concept[45] and its application to the relations among nations, and they sought to establish customary "laws of war and peace"[46] to ameliorate wars and make them less likely. This led to considerations of what authority monarchs or other officials have and don't have, from where that authority derives, and the remedies for the abuse of such authority.[47]

El Renaixement portat una sèrie de filòsofs polítics que escrivien implicava crítiques de les pràctiques de monarques i procurava identificar principis de disseny constitucional seria probable que que en produís més eficaç i només govern des dels seus punts de vista. Això començava amb el ressorgiment del concepte de dret de gents romà [48]. i la seva aplicació a les relacions entre nacions, i procuraven establir "drets normals de guerra i pau" [49]. millorar guerres i fer-los menys probables. Això conduïa a consideracions de què tenen els monarques d'autoritat o uns altres oficials i no tenen, des d'on es deriva aquella autoritat, i els remeis per l'abús de tal autoritat.[50].

A seminal juncture in this line of discourse arose in England from the Civil War, the Cromwellian Protectorate, the writings of Thomas Hobbes, Samuel Rutherford, the Levellers, John Milton, and James Harrington, leading to the debate between Robert Filmer, arguing for the divine right of monarchs, on the one side, and on the other, Henry Neville, James Tyrrell, Algernon Sidney, and John Locke. What arose from the latter was a concept of government being erected on the foundations of first, a state of nature governed by natural laws, then a state of society, established by a social contract or compact, which bring underlying natural or social laws, before governments are formally established on them as foundations.

Un juncture bàsic en aquesta línia de discurs sorgia a Anglaterra de la Guerra Civil, el Protectorat DE Cromwellian, conduint les escriptures de Thomas Hobbes, Samuel Rutherford, el Levellers, John Milton, i James Harrington al debat entre Robert Filmer, que advoca a favor del dret diví de monarques, sobre aquest costat, i en l'altre, Henry Neville, James Tyrrell, Algernon Sidney, i John Locke. Què sorgia de l'últim era un concepte de govern que s'aixecava en les fundacions de primer, un estat de natura governada per lleis naturals, llavors un estat de la societat, establert per un contracte social o compacta, la qual cosa porta drets naturals o socials subjacents, abans que els governs s'estableixin formalment en ells com fundacions.

Along the way several writers examined how the design of government was important, even if the government were headed by a monarch. They also classified various historical examples of governmental designs, typically into democracies, aristocracies, or monarchies, and considered how just and effective each tended to be and why, and how the advantages of each might be obtained by combining elements of each into a more complex design that balanced competing tendencies. Some, such as Montesquieu, also examined how the functions of government, such as legislative, executive, and judicial, might appropriately be separated into branches. The prevailing theme among these writers was that the design of constitutions is not completely arbitrary or a matter of taste. They generally held that there are underlying principles of design that constrain all constitutions for every polity or organization. Each built on the ideas of those before concerning what those principles might be.

Al llarg de la manera uns quants escriptors examinaven com era el disseny de govern important, fins i tot si el govern era encapçalat per un monarca. També classificaven diversos exemples històrics de dissenys governamentals, típicament a democràcies, aristocràcies, o monarquies, i considerava com només i eficaç cadascun atès per ser i per què, i com es podrien obtenir els avantatges de cada un combinant elements de cada un a un disseny més complex que equilibrava tendències que competien. Alguns, com Montesquieu, també examinaven com les funcions de govern, com legislatiu, executiu, i judicial, podria apropiadament ser separat en branques. El tema que prevalia entre aquests escriptors era que el disseny de constitucions no és completament arbitrari o una qüestió de gust. Generalment sostenien que hi ha principis subjacents de disseny que constrenyen totes les constitucions per a tots els polity o organització. Cada un construïa sobre les idees d'aquells abans de pel que fa a què podrien ser aquells principis.

The later writings of Orestes Brownson[51] would try to explain what constitutional designers were trying to do. According to Brownson there are, in a sense, three "constitutions" involved: The first the constitution of nature that includes all of what was called "natural law." The second is the constitution of society, an unwritten and commonly understood set of rules for the society formed by a social contract before it establishes a government, by which it establishes the third, a constitution of government. The second would include such elements as the making of decisions by public conventions called by public notice and conducted by established rules of procedure. Each constitution must be consistent with, and derive its authority from, the ones before it, as well as from a historical act of society formation or constitutional ratification. Brownson argued that a state is a society with effective dominion over a well-defined territory, that consent to a well-designed constitution of government arises from presence on that territory, and that it is possible for provisions of a written constitution of government to be "unconstitutional" if they are inconsistent with the constitutions of nature or society. Brownson argued that it is not ratification alone that makes a written constitution of government legitimate, but that it must also be competently designed and applied.

Escriptures el posteriors d'Orestes Brownson [52]. provaria explicar què estaven intentant els dissenyadors constitucionals fer. Segons Brownson hi ha, en certa manera, tres "constitucions" implicades: El primer el constitució de natura que n'inclou tot del que s'anomenava "llei natural." El segon és el constitució de la societat, un conjunt oral i comunament entès de regles a favor de la societat formada per un contracte social abans que estableixi un govern, pel qual estableix el terç, un constitució de govern . El segon inclouria tals elements com la fabricació de decisions per convencions públiques anomenades per avís públic i dirigides per regles establertes DE PROCEDIMENT. Cada constitució ha de ser coherent amb, i obté la seva autoritat de, aquells abans d'això, així com d'un acte històric de formació de societat o ratificació constitucional. Brownson sostenia que un estat és una societat amb dominion eficaç sobre un territori ben definit, aquell consentiment per una constitució ben dissenyada de govern sorgeix de la presència en aquell territori, i que és possible per provisions d'una constitució escrita de govern ser "anticonstitucional" si són incoherents amb les constitucions de natura o societat. Brownson sostenia que no és ratificació sola que fa legítima una constitució escrita de govern, però allò això ha també estar dissenyat competentment i ser aplicat.

Other writers[53] have argued that such considerations apply not only to all national constitutions of government, but also to the constitutions of private organizations, that it is not an accident that the constitutions that tend to satisfy their members contain certain elements, as a minimum, or that their provisions tend to become very similar as they are amended after experience with their use. Provisions that give rise to certain kinds of questions are seen to need additional provisions for how to resolve those questions, and provisions that offer no course of action may best be omitted and left to policy decisions. Provisions that conflict with what Brownson and others can discern are the underlying "constitutions" of nature and society tend to be difficult or impossible to execute, or to lead to unresolvable disputes.

Uns altres escriptors [54]. haver sostingut que tals consideracions s'apliquen no solament a totes les constitucions nacionals de govern, sinó també a les constitucions d'organitzacions privades, que no és un accident que les constitucions que tendeixen a satisfer els seus membres continguin certs elements, com a mínim, o que les seves provisions tendeixen a tornar-se molt similars mentre s'esmenen després d'experiència amb el seu ús. Les provisions que causen certes classes de qüestions es veuen necessitar per com per resoldre aquelles qüestions, i provisions que s'ofereixen cap curs d'acció no es pot més ben ometre i esquerres provisions addicionals a decisions de política. Les provisions que estan en conflicte amb el que Brownson i altres poden discernir són les "constitucions" subjacents de natura i societat tendeixen a ser difícil o impossible d'executar, o conduir a disputes d'unresolvable.

Constitutional design has been treated as a kind of metagame in which play consists of finding the best design and provisions for a written constitution that will be the rules for the game of government, and that will be most likely to optimize a balance of the utilities of justice, liberty, and security. An example is the metagame Nomic.[55]

Constitucional el disseny ha estat tractat com a classe de metajoc en quin joc consta de descobriment el millor disseny i provisions per una constitució escrita que seran les regles a favor del joc de govern, i serà més probable que que optimitzin un equilibri de les utilitats de justícia, llibertat, i seguretat. Un exemple és el Nomic metajoc.[56].

Governmental constitutions

[modifica]constitucions Governamentals

[modifica]

[[Còpia de File:Red del rus constitution.jpg|polze|post|Còpia Presidencial de la Constitució Russa.]]

Most commonly, the term constitution refers to a set of rules and principles that define the nature and extent of government. Most constitutions seek to regulate the relationship between institutions of the state, in a basic sense the relationship between the executive, legislature and the judiciary, but also the relationship of institutions within those branches. For example, executive branches can be divided into a head of government, government departments/ministries, executive agencies and a civil service/bureaucracy. Most constitutions also attempt to define the relationship between individuals and the state, and to establish the broad rights of individual citizens. It is thus the most basic law of a territory from which all the other laws and rules are hierarchically derived; in some territories it is in fact called "Basic Law".

Més comunament, el terme constitució refereix a un conjunt de regles i principis que defineixen la natura i abast de govern. La majoria de les constitucions procuren regular la relació entre institucions de l'estat, en un sentit bàsic la relació entre l'executiu, legislatura i la magistratura, però també la relació d'institucions dins d'aquelles branques. Per exemple, les branques executives es poden dividir en un cap de govern, departaments/ministeris governamentals, agències executives i un servei/burocràcia Civil. La majoria de les constitucions també intenten definir la relació entre individus i l'estat, i establir els drets amples de ciutadans individuals. És així la llei més bàsica d'un territori de què es deriven jeràrquicament tots els altres drets i regles; en alguns territoris es crida de fet " BASIC LLEI".

Key features

[modifica]trets Clau

[modifica]The following are features of democratic constitutions that have been identified by political scientists to exist, in one form or another, in virtually all national constitutions.

Els següents són trets de constitucions democràtiques que s'han identificat per científics polítics per existir, en una forma o un altre, a virtualment totes les constitucions nacionals.

Codification

[modifica]Codificació

[modifica]A fundamental classification is codification or lack of codification. A codified constitution is one that is contained in a single document, which is the single source of constitutional law in a state. An uncodified constitution is one that is not contained in a single document, consisting of several different sources, which may be written or unwritten.

Una classificació fonamental és codificació o manca de codificació. Una constitució codificada és una que es conté en un document únic, que és la font única de dret constitucional en un estat. Una constitució incodificada és una que no es conté en un document únic, que consta d'unes quantes fonts diferents, que es pot escriure o oral.

Codified constitution

[modifica]constitució Codificada

[modifica]Most states in the world have codified constitutions.

Molts estats al món han codificat constitucions.

Codified constitutions are often the product of some dramatic political change, such as a revolution. The process by which a country adopts a constitution is closely tied to the historical and political context driving this fundamental change. The legitimacy (and often the longevity) of codified constitutions has often been tied to the process by which they are initially adopted.

Les constitucions codificades són sovint el producte d'una mica de canvi polític notable, com una revolució. El procés pel qual un país adopta una constitució és de prop lligat al context històric i polític que condueix aquest canvi fonamental. La legitimitat (i sovint la longevitat) de constitucions codificades s'ha lligat sovint al procés pel qual són inicialment adoptats.

States that have codified constitutions normally give the constitution supremacy over ordinary statute law. That is, if there is any conflict between a legal statute and the codified constitution, all or part of the statute can be declared ultra vires by a court, and struck down as unconstitutional. In addition, exceptional procedures are often required to amend a constitution. These procedures may include: convocation of a special constituent assembly or constitutional convention, requiring a supermajority of legislators' votes, the consent of regional legislatures, a referendum process, and other procedures that make amending a constitution more difficult than passing a simple law.

Estats Units que han codificat constitucions normalment donen la supremacia de constitució sobre llei d'estatut corrent. És a dir, si hi ha algun conflicte entre un estatut legal i la constitució codificada, completament o en part de l'estatut pot ser declarat ultravires al costat d'un jutjat, i fulminava com anticonstitucional. A més a més, s'exigeix sovint que els procediments excepcionals esmenin una constituciÓ. Aquests procediments poden incloure: convocatòria d'una assemblea de component especial o convenció constitucional, que exigeix una supermajoria dels vots dels legisladors, el consentiment de legislatures regionals, un procés de referèndum, i uns altres procediments que fan esmenant una constitució més difícil que el pas una llei simple.

Constitutions may also provide that their most basic principles can never be abolished, even by amendment. In case a formally valid amendment of a constitution infringes these principles protected against any amendment, it may constitute a so-called unconstitutional constitutional law.

Les constitucions també poden estipular que els seus principis més bàsics mai no es poden abolir, ni tan sols per esmena. En cas que una esmena formalment vàlida d'una constitució infringeixi aquests principis protegits contra qualsevol esmena, pot constituir un anomenat dret constitucional anticonstitucional .

Codified constitutions normally consist of a ceremonial preamble, which sets forth the goals of the state and the motivation for the constitution, and several articles containing the substantive provisions. The preamble, which is omitted in some constitutions, may contain a reference to God and/or to fundamental values of the state such as liberty, democracy or human rights.

Les constitucions codificades normalment consten d'un preàmbul cerimonial, que exposa els objectius de l'estat i la motivació per a la constitució, i uns quants articles que contenen les provisions substantives. El preàmbul, que s'omet en algunes constitucions, pot contenir una Referència a déu i/o a valors fonamentals de l'estat com llibertat, democràcia o drets humans.

Uncodified constitution

[modifica]constitució Incodificada

[modifica]

A 2010[update] at least three states have uncodified constitutions: Israel, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Uncodified constitutions (also known as unwritten constitutions) are the product of an "evolution" of laws and conventions over centuries. By contrast to codified constitutions, in the Westminster tradition that originated in England, uncodified constitutions include written sources: e.g. constitutional statutes enacted by the Parliament (House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975, Northern Ireland Act 1998, Scotland Act 1998, Government of Wales Act 1998, European Communities Act 1972 and Human Rights Act 1998); and also unwritten sources: constitutional conventions, observation of precedents, royal prerogatives, custom and tradition, such as always holding the General Election on Thursdays; together these constitute the British constitutional law. In the days of the British Empire, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council acted as the constitutional court for many of the British colonies such as Canada and Australia which had federal constitutions.

A 2010[update] at least three states have uncodified constitutions: Israel, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Uncodified constitutions (also known as unwritten constitutions) are the product of an "evolution" of laws and conventions over centuries. By contrast to codified constitutions, in the Westminster tradition that originated in England, uncodified constitutions include written sources: e.g. constitutional statutes enacted by the Parliament (House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975, Northern Ireland Act 1998, Scotland Act 1998, Government of Wales Act 1998, European Communities Act 1972 and Human Rights Act 1998); and also unwritten sources: constitutional conventions, observation of precedents, royal prerogatives, custom and tradition, such as always holding the General Election on Thursdays; together these constitute the British constitutional law. In the days of the British Empire, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council acted as the constitutional court for many of the British colonies such as Canada and Australia which had federal constitutions.

A 2010[update] com a mínim tres estats han incodificat constitucions: Israel, Nova Zelanda, i el Regne Unit. Les constitucions incodificades (també conegut com constitucions orals) són el producte d'una "evolució" de drets i convencions durant segles. Per contrast a constitucions codificades, en la tradició de Westminster que originat a Anglaterra, les constitucions incodificades inclouen fonts escrites: estatuts p. ex. constitucionals promulgats pel Parlament (Acte De Desqualificació D'house Of Commons 1975, Acte De Northern Ireland 1998, Acte D'escòcia 1998, Govern De L'acte De País De Gal·les 1998, L'Acte De Comunitats 1972 Europeu i L'Acte De Drets Humans 1998); i també fonts orals: convencions constitucionals, observació de precedents, prerrogatives reials, costum i tradició, com sempre celebrar l'Elecció General els dijous; junts aquests constitueixen el Dret constitucional britànic. En els dies de l'Imperi Britànic, el ComitÈ JUDICIAL OF THE PRIVY COUNCIL feia del jutjat constitucional per a moltes de les colònies britàniques com el Canadà i Austràlia que tenien constitucions federals.

Elements of constitutional law in states with uncodified constitutions can be entrenched; for example, sections of the Electoral Act 1993 of New Zealand relating to the maximum term of parliament and how elections are held require a three-quarter majority in the House of Representatives or a simple majority in a referendum to be amended or repealed.

Es poden establir elements de dret constitucional en estats amb constitucions incodificades; per exemple, seccions de l'Acte 1993 Electoral de Nova Zelanda referint al màxim terme de parlament i com se celebren eleccions exigir una majoria de tres quart a l'House of Representatives o una majoria simple en un referèndum per ser esmenat o perquè se'l refaci repicar.

Written versus unwritten; codified versus uncodified

[modifica]Escrit contra oral; codificat contra incodificat

[modifica]The term written constitution is used to describe a constitution that is entirely written, which by definition includes every codified constitution; but not all constitutions based entirely on written documents are codified.

El terme constitució escrita és utilitzat descriure una constitució que s'escriu totalment, que per definició inclou totes les constitucions codificades; però no totes les constitucions basades totalment en documents escrits es codifiquen.

Some constitutions are largely, but not wholly, codified. For example, in the Constitution of Australia, most of its fundamental political principles and regulations concerning the relationship between branches of government, and concerning the government and the individual are codified in a single document, the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia. However, the presence of statutes with constitutional significance, namely the Statute of Westminster, as adopted by the Commonwealth in the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942, and the Australia Act 1986 means that Australia's constitution is not contained in a single constitutional document. The Constitution of Canada, which evolved from the British North America Acts until severed from nominal British control by the Canada Act 1982 (analogous to the Australia Act 1986), is a similar example. Canada's constitution consists of almost 30 different statutes

Algunes constitucions són en gran part, però no completament, codificaven. Per exemple, a la Constitució d'Austràlia, la majoria dels seus principis polítics fonamentals i regulacions pel que fa a la relació entre branques de govern, i pel que fa al govern i l'individu es codifiquen en un document únic, la Constitució de la Commonwealth d'Austràlia. Tanmateix, la presència d'estatuts amb la importància constitucional, és a dir l'Estatut Of Westminster, com adoptat per la Mancomunitat a l'Estatut De L'acte De Westminster Adoption 1942, i l'Acte D'austràlia 1986 mitjà que la constitució d'Austràlia no es conté en un document constitucional únic. LA ConstituciÓ De CanadÀ, que es convertia dels actes d'amÈRICA DEL NORD BRITÀNICS fins que tallats des de control britànic nominal prop de l'Acte Del Canadà 1982 (anàleg a l'Acte d'Austràlia 1986), és un exemple similar. La constitució del Canadà CONSTA DE GAIREBÉ 30 ESTATUTS DIFERENTS

The terms written constitution and codified constitution are often used interchangeably, as are unwritten constitution and uncodified constitution, although this usage is technically inaccurate. Strictly speaking, unwritten constitution is never an accurate synonym for uncodified constitution, because all modern democratic constitutions mainly comprise written sources, even if they have no different legal status than ordinary statutes. Another, correct, term used is formal (or formal written) constitution, for example in the following context: "The United Kingdom has no formal [written] constitution" (which does not preclude a constitution based on documents but not codified).

Els termes constitució escrita i constitució codificada són sovint utilitzat de manera intercanviable, com són constitució oral i constitució incodificada, encara que aquest ús és tècnicament inexacte. En rigor constitució oral és mai un sinònim acurat per constitució incodificada, perquè totes les constitucions democràtiques modernes principalment comprenen fonts escrites, fins i tot si no tenen cap situació jurídica diferent que estatuts corrents. Un altre terme, correcte, utilitzat és formal (o formal escrit ) constitució, per exemple en el següent context: "El Regne Unit no té cap constitució formal [escrit]" (quin no impedeix una constitució basada en documents però no codificada).

Entrenchment

[modifica]Trinxera

[modifica]Plantilla:Original research Plantilla:Ref improve section

The presence or lack of entrenchment is a fundamental feature of constitutions. An entrenched constitution cannot be altered in any way by a legislature as part of its normal business concerning ordinary statutory laws, but can only be amended by a different and more onerous procedure. There may be a requirement for a special body to be set up, or the proportion of favourable votes of members of existing legislative bodies may be required to be higher to pass a constitutional amendment than for statutes. The entrenched clauses of a constitution can create different degrees of entrenchment, ranging from simply excluding constitutional amendment from the normal business of a legislature, to making certain amendments either more difficult than normal modifications, or forbidden under any circumstances.

La presència o manca de trinxera és un tret fonamental de constitucions. Una constitució establerta no es pot canviar de cap manera per una legislatura com part del seu negoci normal pel que fa a drets reglamentaris corrents, sinó que només pot ser esmenada per un procediment diferent i més onerós. Hi pot haver un requisit d'un cos especial per ser establert, o la proporció de vots favorables de membres d'existir cossos legislatius poden ser demanats ser més alt per aprovar una esmena constitucional que per a estatuts. Les clàusules establertes d'una constitució poden crear graus diferents de trinxera, estenent-se de simplement excepte esmena constitucional des del negoci normal d'una legislatura, a fer certes esmenes o més difícils que les modificacions normals, o prohibides en algunes circumstàncies.

Entrenchment is an inherent feature in most codified constitutions. A codified constitution will incorporate the rules which must be followed for the constitution itself to be changed.

La trinxera és un tret inherent en la majoria de les constitucions codificades. Una constitució codificada incorporarà les regles que s'han de seguir per a la constitució mateixa per ser canviada.

The US constitution is an example of an entrenched constitution, and the UK constitution is an example of a constitution that is not entrenched (or codified). In some states the text of the constitution may be changed; in others the original text is not changed, and amendments are passed which add to and may override the original text and earlier amendments.

El Nosaltres constitució és un exemple d'una constitució establerta, i la constitució Uk és un exemple d'una constitució que no s'estableix (o codificat). En alguns estats el text de la constitució es pot canviar; en altres el text original no es canvia, i LES esmenes s'aproven que se sumen a i poden invalidar el text original i esmenes anteriors.

Procedures for constitutional amendment vary between states. In a nation with a federal system of government the approval of a majority of state or provincial legislatures may be required. Alternatively, a national referendum may be required. Details are to be found in the articles on the constitutions of the various nations and federal states in the world.

Els procediments per a l'esmena constitucional varien entre estats. En una nació amb un sistema federal de govern l'aprovació d'una majoria de legislatures estatals o provincials es pot exigir. Alternativament, es pot exigir un referèndum nacional. Els detalls són ser trobats als articles sobre les constitucions de les diverses nacions i estats federals al món.

In constitutions that are not entrenched, no special procedure is required for modification. Lack of entrenchment is a characteristic of uncodified constitutions; the constitution is not recognised with any higher legal status than ordinary statutes. In the UK, for example laws which modify written or unwritten provisions of the constitution are passed on a simple majority in Parliament. No special "constitutional amendment" procedure is required. The principle of parliamentary sovereignty holds that no sovereign parliament may be bound by the acts of its predecessors;[57] and there is no higher authority that can create law which binds Parliament. The sovereign is nominally the head of state with important powers, such as the power to declare war; the uncodified and unwritten constitution removes all these powers in practice.

En constitucions que no s'estableixen, cap procediment especial no s'exigeix per a la modificació. La manca de trinxera és una característica de constitucions incodificades; la constitució no es reconeix amb cap situació jurídica més alta que els estatuts corrents. A l'Uk, per exemple els drets que modifiquen provisions escrites o orals de la constitució es passen sobre una majoria simple en Parlament. Cap "esmena constitucional" especial el procediment és demanat. El principi de sobirania parlamentària sosté que cap parlament de sobirans no pot ser lligat pels actes dels seus predecessors; [58]. i no hi ha autoritat no més alta que pot crear llei que lliga Parlament. El sobirà és nominalment el cap d'estat amb poders importants, com el poder de declarar guerra; la constitució incodificada i oral treu tots aquests poders en la pràctica.

In practice democratic governments do not use the lack of entrenchment of the constitution to impose the will of the government or abolish all civil rights, as they could in theory do, but the distinction between constitutional and other law is still somewhat arbitrary, usually following historical principles embodied in important past legislation. For example, several British Acts of Parliament such as the Bill of Rights, Human Rights Act and, prior to the creation of Parliament, Magna Carta are regarded as granting fundamental rights and principles which are treated as almost constitutional. Several rights that in another state might be guaranteed by constitution have indeed been abolished or modified by the British parliament in the early 21st century, including the unconditional right to trial by jury, the right to silence without prejudicial inference, permissible detention before a charge is made extended from 24 hours to 42 days, and the right not to be tried twice for the same offence.

En la pràctica els governs democràtics no utilitzen la manca de trinxera de la constitució per imposar la voluntat del govern o per abolir tots els drets civils, mentre podrien en teoria fer, però la distinció entre llei constitucional i altre són principis històrics una mica arbitraris, normalment següents quiets compresos en la legislació passada important. Per exemple, uns quants Actes britànics de parlament com la Declaració De Drets, Acte de Drets Humans i, abans de la creació de Parlament, Magna Carta es veuen com concedir drets fonamentals i principis que es tracten com gairebé constitucional. Uns quants drets que en un altre estat podrien ser garantits per constitució s'han abolit en efecte o han estat modificats pel parlament britànic a primers del 21è segle, incloent-hi l'incondicional bé a judici per jurat, el dret a silenci sense inferència prejudicial, la detenció permissible abans d'una càrrega es fa estès de 24 hores a 42 dies, i el CORRECTE per NO SER VOLGUDES DUES VEGADES EL MATEIX DELICTE.

Absolutely unmodifiable articles

[modifica]articles Absolutament immodificables

[modifica]The strongest level of entrenchment exists in those constitutions that state that some of their most fundamental principles are absolute, i.e. certain articles may not be amended under any circumstances. An amendment of a constitution that is made consistently with that constitution, except that it violates the absolute non-modifiability, can be called an unconstitutional constitutional law. Ultimately it is always possible for a constitution to be overthrown by internal or external force, for example, a revolution (perhaps claiming to be justified by the right to revolution) or invasion.

El nivell més fort de trinxera existeix en aquelles constitucions que manifesten que alguns dels seus principis més fonamentals són absoluts, i.e. certs que els articles puguin no esmenar-se en cap circumstància. Una esmena d'una constitució que es fa coherentment amb aquella constitució, excepte que viola el no-modifiability absolut, es pot anomenar un dret constitucional anticonstitucional . En el fons és sempre possible que una constitució sigui enderrocada per la força interna o externa, per exemple, una revolució (potser afirmant ser justificada pel dret a revoluciÓ) o invasió.

An example of absolute unmodifiability is the German Federal Constitution. This states in Articles 1 and 20 that the state powers, which derive from the people, must protect human dignity on the basis of human rights, which are directly applicable law binding on all three branches of government, which is a democratic and social federal republic; that legislation must be according to the rule of law; and that the people have the right of resistance as a last resort against any attempt to abolish the constitutional order. Article 79, Section 3 states that these articles cannot be changed, even according to the methods of amendment defined elsewhere in the document.

Un exemple d'unmodifiability absolut és la Constitució Federal Alemanya. Això els estats en Articles 1 i 20 que l'estat alimenta, la qual cosa es deriva de la gent, han de protegir dignitat humana sobre la base de drets humans, que són enquadernació de llei directament aplicable en les tres branques de govern, que és una república federal democràtica i social; aquella legislació ha de ser segons la norma jurídica; i que la gent té el dret de resistència com a últim recurs en contra de qualsevol intent d'abolir l'ordre constitucional. atrinxerat Article 79, Secció 3|ATRINXERAT ARTICLE 79, SECCIÓ 3 estats que aquests articles no es poden canviar, ni tan sols segons els mètodes d'esmena definida en qualsevol altre lloc en el document.

Another example is the Constitution of Honduras, which has an article stating that the article itself and certain other articles cannot be changed in any circumstances. Article 374 of the Honduras Constitution asserts this unmodifiability, stating, "It is not possible to reform, in any case, the preceding article, the present article, the constitutional articles referring to the form of government, to the national territory, to the presidential period, the prohibition to serve again as President of the Republic, the citizen who has performed under any title in consequence of which she/he cannot be President of the Republic in the subsequent period."[59] This unmodifiability article played an important role in the 2009 Honduran constitutional crisis.

Un altre exemple és la Constitució D'hondures, que té un article que manifesta que l'article mateix i certs altres articles no es poden canviar en cap circumstància. L'article 374 de la Constitució d'Hondures afirma aquest unmodifiability, que manifesta, "No és possible reformar, en cap cas, l'article anterior, l'article present, referint-se els articles constitucionals a la forma de govern, al territori nacional, al període presidencial, la prohibició per complir una altra vegada com President de la República, el ciutadà que ha actuat sota qualsevol títol en conseqüència del qual ell/ell no pot ser President de la República en el subsegüent període." .[59] Aquest article d'unmodifiability jugava un paper important en la Crisi constitucional hondurenya de 2009.

Distribution of sovereignty

[modifica]Distribució de sobirania

[modifica]

Constitutions also establish where sovereignty is located in the state. There are three basic types of distribution of sovereignty according to the degree of centralisation of power: unitary, federal, and confederal. The distinction is not absolute.

Les constitucions també estableixen on sobirania és localitzat en l'estat. Hi ha tres tipus bàsics de distribució de sobirania segons el grau de centralització de poder: unitari, federal, i confederal. La distinció no és absoluta.

In a unitary state, sovereignty resides in the state itself, and the constitution determines this. The territory of the state may be divided into regions, but they are not sovereign and are subordinate to the state. In the UK, the constitutional doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty dictates than sovereignty is ultimately contained at the centre. Some powers have been devolved to Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales (but not England). Some unitary states (Spain is an example) devolve more and more power to sub-national governments until the state functions in practice much like a federal state.

En un estat unitari, la sobirania resideix a l'estat mateix, i la constitució determina això. El territori de l'estat es pot dividir en regions, però no són sobirà i estan subordinats a l'estat. A l'Uk, la doctrina constitucional de Sobirania parlamentària mana que sobirania és en el fons contingut en el centre. Alguns poders S'Han transferit a Northern Ireland, Escòcia, i País de gal·les (però no ANGLATERRA). Alguns estats unitaris (Espanya és un exemple) transfereixen més i més poder a governs subnacionals fins que l'estat funcioni en la pràctica molt com un estat federal.

A federal state has a central structure with at most a small amount of territory mainly containing the institutions of the federal government, and several regions (called states, provinces, etc.) which comprise the territory of the whole state. Sovereignty is divided between the centre and the constituent regions. The constitutions of Canada and the United States establish federal states, with power divided between the federal government and the provinces or states. Each of the regions may in turn have its own constitution (of unitary nature).

Un estat federal té una estructura central amb com a màxim principalment contenint una quantitat petita de territori les institucions del govern federal, i unes quantes regions (anomenat estats, províncies, etc.) quin comprèn el territori de l'estat sencer. La sobirania es divideix entre el centre i les regions de component. Les constitucions del Canadà i els Estats Units estableixen estats federals, amb poder dividit entre el govern federal i les províncies o estats. Cada un de les regions pot a canvi tenir la seva pròpia constitució (de natura unitària).

A confederal state comprises again several regions, but the central structure has only limited coordinating power, and sovereignty is located in the regions. Confederal constitutions are rare, and there is often dispute to whether so-called "confederal" states are actually federal.

Un estat confederal comprèn una altra vegada unes quantes regions, però l'estructura central només ha limitat poder que es coordina, i sobirania és localitzat a les regions. Les constitucions confederals són rares, i hi ha sovint disputa a si els anomenats estats "confederals" són de fet federals.

To some extent a group of states which do not constitute a federation as such may by treaties and accords give up parts of their sovereignty to a supranational entity. For example the countries comprising the European Union have agreed to abide by some Union-wide measures which restrict their absolute sovereignty in some ways, e.g., the use of the metric system of measurement instead of national units previously used.

En alguna mesura un grup d'estats que no constitueixen una federació com a tal pot per tractats i acords deixen parts de la seva sobirania a una entitat supranacional. Per exemple els països que comprenen la Unió Europea han acceptat que per respectar algunes mesures àmplies d'Unió que restringeixen la seva sobirania absoluta de diverses maneres, p. ex., l'ús del sistema mètric de mesura en comptes d'unitats nacionals prèviament utilitzava.

Separation of powers

[modifica]Separació de poders

[modifica]

Constitutions usually explicitly divide power between various branches of government. The standard model, described by the Baron de Montesquieu, involves three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial. Some constitutions include additional branches, such as an auditory branch. Constitutions vary extensively as to the degree of separation of powers between these branches.

Les constitucions normalment explícitament divideixen poder entre diverses branques de govern. El model estàndard, descrit pel BarÓ DE MONTESQUIEU, implica tres branques de govern: executiu, legislatiu i judicial. Algunes constitucions inclouen branques addicionals, com una branca auditiva. Les constitucions varien extensament pel que fa al grau de separació de poders entre aquestes branques.

Lines of accountability

[modifica]Línies de responsabilitat

[modifica]In presidential and semi-presidential systems of government, department secretaries/ministers are accountable to the president, who has patronage powers to appoint and dismiss ministers. The president is accountable to the people in an election.